BOSTON — Before becoming an improbable catalyst for the St. Louis Blues’ improbable stampede to the Stanley Cup finals, Jordan Binnington had the coolest goalie mask in the ECHL.

In 2013, he reported to the Kalamazoo Wings, two levels below the N.H.L., with an image of the actor Will Smith — circa “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air” days of the early 1990s — adorning the left side of his cage. His coach, Nick Bootland, expected a fascinating back story — that Binnington must have met Smith once or something.

Nope. Binnington just thought Smith was “awesome.”

Laughing as he recounted that story last week, Bootland remarked how that quip, in its brevity and I-don’t-give-a-flying-potato-what-you-think conviction, seemed to capture Binnington’s spirit. Another of his bon mots, dispensed after a victory in late February, spawned a T-shirt popular in St. Louis: Do I look nervous?

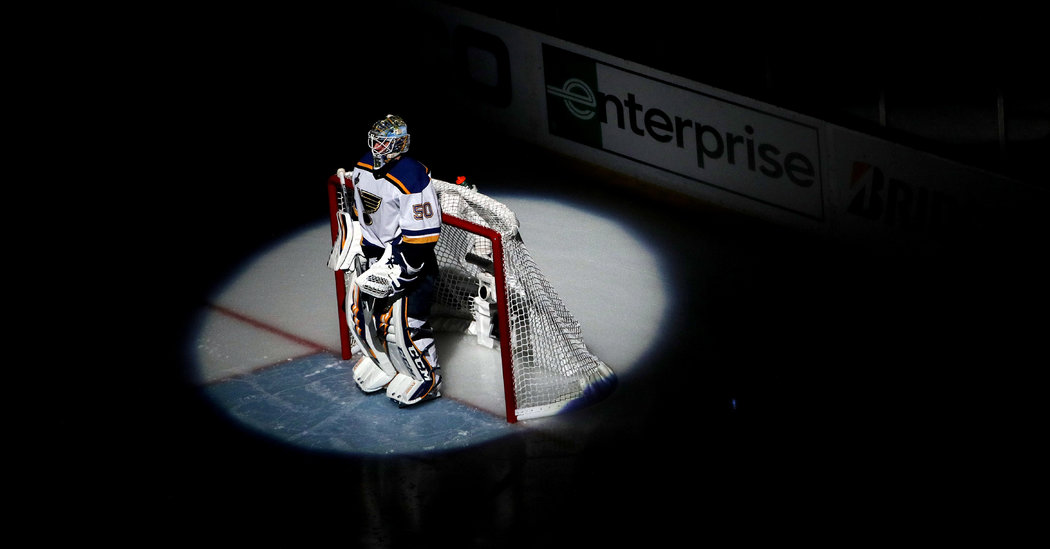

The answer to that rhetorical question was the same then as it has been throughout the N.H.L. playoffs, as it was Monday night, when across the final two periods of the Blues’ 4-2 Game 1 loss to the Boston Bruins it seemed as if Binnington was the only one who kept his composure.

The Blues lost in spite — not because — of their rookie goaltender, sullying their first finals game since 1970 by giving Boston five power plays, squandering a two-goal lead and going 12 minutes 49 seconds without a shot on net during one stretch bridging the second and third periods.

In this season of firsts for Binnington — first N.H.L. start, first victory, first time leading the league in goals-against average — he stopped 34 of 37 shots, thwarting seven of nine high-danger scoring chances, according to Natural Stat Trick, in his Stanley Cup finals debut.

But he couldn’t corral Zdeno Chara’s soft wrister from the point early in the third, igniting a sequence that produced Sean Kuraly’s go-ahead goal. Binnington then watched from the bench as Boston added a late empty-netter.

“It’s not always going to be perfect,” he said.

These last four and a half months have thrust Binnington into a realm of celebrity in St. Louis once occupied by another cult hero plucked from obscurity: quarterback Kurt Warner, who stocked shelves at an Iowa supermarket before delivering the Gateway City a Super Bowl title with the Rams.

Binnington logged more than 200 minor league appearances before making, at age 25, his first N.H.L. start. He shut out the Philadelphia Flyers on Jan. 7, five days after St. Louis plunged to the bottom of the league standings.

Binnington began this season as the No. 4 goalie in the organization, which sounds bad but, really, could have been worse.

At least he wasn’t fifth, as he was heading into last season, when he wondered whether his N.H.L. future, if he had one at all, would be in St. Louis.

“It would be disingenuous to say that this was all part of the master plan,” Blues General Manager Doug Armstrong said.

Not all goalies make their first N.H.L. start at 19, as the Hall of Famer Grant Fuhr did with Edmonton; or become mainstays by 22, as Carey Price did with Montreal; or win two Stanley Cups by 23, as Matt Murray did with Pittsburgh. Some take longer to develop, even if they and their employers would prefer otherwise.

Binnington, drafted in the third round in 2011, lingered in juniors and the minors for four years before an uneven minor league season with the Chicago Wolves shoved him down the Blues’ hierarchy of goalie prospects. He went out at night a lot. He hadn’t consistently demonstrated the discipline and commitment that the job demanded, and he knew it.

The metamorphosis started two summers ago, at the rink in northern Toronto where the former Maple Leafs strength and conditioning coach Matt Nichol operates his off-season program. Nichol likened the weight room to a dungeon, but it has been sufficient for Edmonton’s Connor McDavid, a league most valuable player and scoring champion.

There, a year earlier, Binnington had befriended Andy Chiodo, a goalie whose professional career was concluding and whose work ethic he had come to admire. With his career teetering, Binnington confided in Chiodo, by then a goalie coach for Nichol, a desire to improve his discipline and lifestyle habits.

“That summer was really powerful,” Chiodo, now the Penguins’ goalie development coach, said in an interview last week. “He was open about what he wanted.”

From May to September, five days a week — and sometimes six — Binnington worked on body and mind. Surrounded by N.H.L. captains and Cup winners, he learned critical differences: between training and exercising, eating and fueling, practicing and preparing with intent. He thwarted McDavid and Dallas Stars star Tyler Seguin on the ice and won his peers’ respect in the weight room.

In one conversation with Binnington, Nichol relayed how Houston Texans defensive end J.J. Watt, when asked whether he was bothered by teammates criticizing his perceived lack of a social life, said he could excel at football for only a finite period; he could drink all the beer he wanted later.

Nichol also shared how when Watt used the weight room during a visit to Toronto, he asked if he could come earlier than his normal 6 a.m. session because of a 9 a.m. engagement about an hour away. Told yes, Watt proceeded to estimate the duration of every task — breakfast, a coffee stop, the length of his drive, accounting for potential traffic — before settling on 4 a.m.

“To see a guy like that — his entire life revolved around his training,” Nichol said. “For Jordan, it was the realization that I’m not the fun police. He’s a guy that’s had his fun. In order to achieve the things he wanted, it had to be a full-time effort.”

By then, though, another young goalie, Ville Husso, had vaulted ahead of Binnington in the Blues’ organization. At the beginning of last season the Blues demoted him from the American Hockey League to the ECHL, but he refused to go.

Instead, they lent him to the A.H.L. affiliate of, yes, the Bruins, in Providence, R.I., where he played well — but not well enough to persuade the Blues that he merited more than one period of work in the 2018 preseason.

He began this season backing up Husso with the San Antonio Rampage, but when Husso struggled, Binnington shined.

“We were a different team when he was in net,” said Rampage Coach Drew Bannister, who also assisted on Binnington’s junior team for a season. “He took advantage of an opportunity that probably wasn’t going to be there.”

After being called up to the Blues in January, Binnington stabilized a team careering out of contention, infused it with confidence, and backstopped it to 12 playoff wins. Emboldened, he has since moved out of temporary lodging in St. Louis into extended-stay accommodations, and he hopes to return home Thursday with the series tied.

If not, if the Blues need to win four of the final five games to hoist their first Stanley Cup, then that would reflect the theme of their season, of Binnington’s career. It would be the most awesome thing of all.

Follow Ben Shpigel on Twitter: @benshpigel.